Internships For Video Game Design Las Vegad

Largest city in Nevada

City in Nevada, United States

| Las Vegas, Nevada | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| From top, left to right: Downtown Las Vegas, World Market Center, Stratosphere Tower Las Vegas, Las Vegas Strip, Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, Clark County Government Center. | |

| Flag Seal | |

| Etymology: Spanish: Las vegas (English: The meadows) | |

| Nickname(s): "Vegas",[1] "Sin City", "City of Lights", "The Gambling Capital of the World",[2] "The Entertainment Capital of the World", "Capital of Second Chances",[3] "The Marriage Capital of the World", "The Silver City", "America's Playground" | |

Interactive map of Las Vegas | |

| Coordinates: 36°10′30″N 115°08′11″W / 36.17500°N 115.13639°W / 36.17500; -115.13639 Coordinates: 36°10′30″N 115°08′11″W / 36.17500°N 115.13639°W / 36.17500; -115.13639 | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Nevada |

| County | Clark |

| Founded | May 15, 1905 |

| Incorporated | March 16, 1911 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Carolyn Goodman (I) |

| • City Council | Members

|

| • City manager | Scott D. Adams |

| Area [4] | |

| • City | 141.84 sq mi (367.36 km2) |

| • Land | 141.78 sq mi (367.22 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.14 km2) |

| Elevation | 2,001 ft (610 m) |

| Population (2020)[5] | |

| • City | 641,903 |

| • Rank | 26th in the United States 1st in Nevada |

| • Density | 4,527.46/sq mi (1,748.01/km2) |

| • Metro [6] | 2,265,461 (29th) |

| Demonym(s) | Las Vegan |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| Area code(s) | 702 & 725 |

| FIPS code | 32-40000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 847388 |

| Major airport | LAS |

| Interstate Highways | |

| Other major highways | |

| Website | lasvegasnevada |

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 26th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas Valley metropolitan area and is the largest city within the greater Mojave Desert.[7] Las Vegas is an internationally renowned major resort city, known primarily for its gambling, shopping, fine dining, entertainment, and nightlife. The Las Vegas Valley as a whole serves as the leading financial, commercial, and cultural center for Nevada.

The city bills itself as The Entertainment Capital of the World, and is famous for its mega casino-hotels and associated activities. It is a top three destination in the United States for business conventions and a global leader in the hospitality industry, claiming more AAA Five Diamond hotels than any other city in the world.[8] [9] [10] Today, Las Vegas annually ranks as one of the world's most visited tourist destinations.[11] [12] The city's tolerance for numerous forms of adult entertainment earned it the title of "Sin City",[13] and has made Las Vegas a popular setting for literature, films, television programs, and music videos.

Las Vegas was settled in 1905 and officially incorporated in 1911. At the close of the 20th century, it was the most populated North American city founded within that century (a similar distinction was earned by Chicago in the 19th century). Population growth has accelerated since the 1960s, and between 1990 and 2000 the population nearly doubled, increasing by 85.2%. Rapid growth has continued into the 21st century, and according to the United States Census Bureau, the city had 641,903 residents in 2020,[5] with a metropolitan population of 2,227,053.[14]

As with most major metropolitan areas, the name of the primary city ("Las Vegas" in this case) is often used to describe areas beyond official city limits. In the case of Las Vegas, this especially applies to the areas on and near the Las Vegas Strip, which are actually located within the unincorporated communities of Paradise and Winchester.[15] [16]

Toponymy

The area was named Las Vegas, which is Spanish for "the meadows", as it featured abundant wild grasses, as well as the desert spring waters needed by westward travelers.[17]

History

Southern Paiutes at Moapa wearing traditional Paiute basket hats with Paiute cradleboard and rabbit robe

Nomadic Paleo-Indians traveled to Las Vegas 10,000 years ago, leaving behind petroglyphs. Anasazi and Paiute tribes followed at least 2,000 years ago.

A young Mexican scout named Rafael Rivera is credited as the first non-Native American to encounter the valley, in 1829.[18] [19] [20] [21] Trader Antonio Armijo led a 60-man party along the Spanish Trail to Los Angeles, California in 1829.[22] [19] The year 1844 marked the arrival of John C. Frémont, whose writings helped lure pioneers to the area. Downtown Las Vegas's Fremont Street is named after him.

Eleven years later, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints chose Las Vegas as the site to build a fort halfway between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles, where they would travel to gather supplies. The fort was abandoned several years afterward. The remainder of this Old Mormon Fort can still be seen at the intersection of Las Vegas Boulevard and Washington Avenue.

Las Vegas was founded as a city in 1905, when 110 acres (45 ha) of land adjacent to the Union Pacific Railroad tracks were auctioned in what would become the downtown area. In 1911, Las Vegas was incorporated as a city.[23]

1931 was a pivotal year for Las Vegas. At that time, Nevada legalized casino gambling and reduced residency requirements for divorce to six weeks. This year also witnessed the beginning of construction on nearby Hoover Dam. The influx of construction workers and their families helped Las Vegas avoid economic calamity during the Great Depression. The construction work was completed in 1935.

In late 1941, Las Vegas Army Airfield was established. Renamed Nellis Air Force Base in 1950, it is now home to the United States Air Force Thunderbirds aerobatic team.[24]

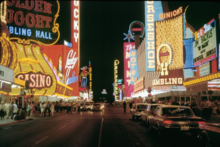

Following World War II, lavishly decorated hotels, gambling casinos, and big-name entertainment became synonymous with Las Vegas.

This view of downtown Las Vegas shows a mushroom cloud in the background. Scenes such as this were typical during the 1950s. From 1951 to 1962, the government conducted 100 atmospheric tests at the nearby Nevada Test Site.[25]

In 1951, nuclear weapons testing began at the Nevada Test Site, 65 miles (105 km) northwest of Las Vegas. During this time, the city was nicknamed the "Atomic City". Residents and visitors were able to witness the mushroom clouds (and were exposed to the fallout) until 1963 when the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty required that nuclear tests be moved underground.[25]

In 1955, the Moulin Rouge Hotel opened and became the first racially integrated casino-hotel in Las Vegas.

The iconic "Welcome to Las Vegas" sign, which has never been located within municipal limits, was created in 1959 by Betty Willis.[26]

During the 1960s, corporations and business tycoons such as Howard Hughes were building and buying hotel-casino properties. Gambling was referred to as "gaming", which transitioned it into a legitimate business. Learning from Las Vegas, published during this era, asked architects to take inspiration from the city's highly decorated buildings, helping to start the postmodern architecture movement.

The year 1995 marked the opening of the Fremont Street Experience, in Las Vegas's downtown area. This canopied five-block area features 12.5 million LED lights and 550,000 watts of sound from dusk until midnight during shows held at the top of each hour.

Due to the realization of many revitalization efforts, 2012 was dubbed "The Year of Downtown". Projects worth hundreds of millions of dollars made their debut at this time, including the Smith Center for the Performing Arts, the DISCOVERY Children's Museum, the Mob Museum, the Neon Museum, a new City Hall complex, and renovations for a new Zappos.com corporate headquarters in the old City Hall building.[17] [27]

Geography

Astronaut photograph of Las Vegas at night

Las Vegas is situated within Clark County, in a basin on the floor of the Mojave Desert,[28] and is surrounded by mountain ranges on all sides. Much of the landscape is rocky and arid, with desert vegetation and wildlife. It can be subjected to torrential flash floods, although much has been done to mitigate the effects of flash floods through improved drainage systems.[29]

The peaks surrounding Las Vegas reach elevations of over 10,000 feet (3,000 m), and act as barriers to the strong flow of moisture from the surrounding area. The elevation is approximately 2,030 ft (620 m) above sea level. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 135.86 sq mi (351.9 km2), of which 135.81 sq mi (351.7 km2) is land and 0.05 sq mi (0.13 km2) (0.03%) is water.

After Alaska and California, Nevada is the third most seismically active state in the U.S. It has been estimated by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) that over the next 50 years, there is a 10–20% chance of an M6.0 or greater earthquake occurring within 50 km (31 mi) of Las Vegas.[30]

Within the city, there are many lawns, trees and other greenery. Due to water resource issues, there has been a movement to encourage xeriscapes. Another part of conservation efforts is scheduled watering days for residential landscaping. A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency grant in 2008 funded a program that analyzed and forecast growth and environmental impacts through the year 2019.

Climate

Las Vegas has a subtropical hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification: BWh), typical of the Mojave Desert in which it lies. This climate is typified by long, extremely hot summers; warm transitional seasons; and short winters with mild days and cool nights. There is abundant sunshine throughout the year, with an average of 310 sunny days and bright sunshine during 86% of all daylight hours.[31] [32] Rainfall is scarce, with an average of 4.2 in (110 mm) dispersed between roughly 26 total rainy days per year.[33] Las Vegas is among the sunniest, driest, and least humid locations in North America, with exceptionally low dew points and humidity that sometimes remain below 10%.[34]

The summer months of June through September are extremely hot, though moderated by extremely low humidity. July is the hottest month, with an average daytime high of 104.5 °F (40.3 °C). On average, 137 days per year reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C), of which 78 days reach 100 °F (38 °C) and 10 days reach 110 °F (43 °C). During the peak intensity of summer, overnight lows frequently remain above 80 °F (27 °C), and occasionally above 85 °F (29 °C).[31] While most summer days are consistently hot, dry, and cloudless, the North American Monsoon sporadically interrupts this pattern and brings more cloud cover, thunderstorms, lightning, increased humidity, and brief spells of heavy rain. The window of opportunity for the monsoon to affect Las Vegas usually falls between July and August, although this is inconsistent and varies considerably in its impact from year to year. Summer in Las Vegas is marked by a significant diurnal variation; while less extreme than other parts of the state, nighttime lows in Las Vegas are often 30 °F (16.7 °C) or more lower than daytime highs.[35]

Las Vegas winters are short and generally very mild, with chilly (but rarely cold) daytime temperatures. As in all seasons, sunshine is abundant. December is both the year's coolest and cloudiest month, with an average daytime high of 56.9 °F (13.8 °C) and sunshine occurring during 78% of its daylight hours. Winter evenings are defined by clear skies and swift drops in temperature after sunset, with overnight minima averaging around 40 °F (4.4 °C) in December and January. Owing to its elevation that ranges from 2,000 to 3,000 feet (610 to 910 m), Las Vegas experiences markedly cooler winters than other areas of the Mojave Desert and the adjacent Sonoran Desert that are closer to sea level. Consequently, the city records freezing temperatures an average of 10 nights per winter. However, it is exceptionally rare for temperatures to reach or fall below 25 °F (−4 °C), or for temperatures to remain below 45 °F (7 °C) for an entire day.[31] Most of the annual precipitation falls during the winter months, but even February, the wettest month, averages only four days of measurable rain. The mountains immediately surrounding the Las Vegas Valley accumulate snow every winter, but significant accumulation within the city is rare, although moderate accumulations do occur every few years. The most recent accumulations occurred on February 18, 2019, when parts of the city received about 1 to 2 inches (2.5 to 5.1 cm) of snow[36] and on February 20 when the city received almost 0.5 inches (1.3 cm).[37] Other recent significant snow accumulations occurred on December 25, 2015, and December 17, 2008.[38] Unofficially, Las Vegas' largest snowfall on record was the 12 inches (30 cm) that fell in 1909.[39]

The highest temperature officially observed for Las Vegas, as measured at McCarran International Airport, is 117 °F (47 °C), reached July 10, 2021, the last of five occasions.[31] Conversely, the lowest temperature was 8 °F (−13 °C), recorded on two days: January 25, 1937, and January 13, 1963.[31] However, the highest temperature ever measured within the city of Las Vegas was 118 °F (48 °C) on July 26, 1931.[40] The official record hot daily minimum is 95 °F (35 °C) on July 19, 2005, and July 1, 2013, while, conversely, the official record cold daily maximum is 28 °F (−2 °C) on January 8 and 21, 1937.[31]

Due to concerns about climate change in the wake of a 2002 drought, daily water consumption has been reduced from 314 US gallons (1,190 l) per resident in 2003 to around 205 US gallons (780 l) in 2015.[41]

| Climate data for McCarran International Airport (Paradise, Nevada), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1937–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) | 87 (31) | 92 (33) | 99 (37) | 109 (43) | 117 (47) | 117 (47) | 116 (47) | 114 (46) | 103 (39) | 87 (31) | 78 (26) | 117 (47) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.7 (20.4) | 74.2 (23.4) | 84.3 (29.1) | 93.6 (34.2) | 101.8 (38.8) | 110.1 (43.4) | 112.9 (44.9) | 110.3 (43.5) | 105.0 (40.6) | 94.6 (34.8) | 80.5 (26.9) | 67.9 (19.9) | 113.6 (45.3) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 58.5 (14.7) | 62.9 (17.2) | 71.1 (21.7) | 78.5 (25.8) | 88.5 (31.4) | 99.4 (37.4) | 104.5 (40.3) | 102.8 (39.3) | 94.9 (34.9) | 81.2 (27.3) | 67.1 (19.5) | 56.9 (13.8) | 80.5 (26.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 49.5 (9.7) | 53.5 (11.9) | 60.8 (16.0) | 67.7 (19.8) | 77.3 (25.2) | 87.6 (30.9) | 93.2 (34.0) | 91.7 (33.2) | 83.6 (28.7) | 70.4 (21.3) | 57.2 (14.0) | 48.2 (9.0) | 70.1 (21.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 40.5 (4.7) | 44.1 (6.7) | 50.5 (10.3) | 56.9 (13.8) | 66.1 (18.9) | 75.8 (24.3) | 82.0 (27.8) | 80.6 (27.0) | 72.4 (22.4) | 59.6 (15.3) | 47.3 (8.5) | 39.6 (4.2) | 59.6 (15.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 29.8 (−1.2) | 32.9 (0.5) | 38.7 (3.7) | 45.2 (7.3) | 52.8 (11.6) | 62.2 (16.8) | 72.9 (22.7) | 70.8 (21.6) | 60.8 (16.0) | 47.4 (8.6) | 35.2 (1.8) | 29.0 (−1.7) | 27.4 (−2.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 8 (−13) | 16 (−9) | 19 (−7) | 31 (−1) | 38 (3) | 48 (9) | 56 (13) | 54 (12) | 43 (6) | 26 (−3) | 15 (−9) | 11 (−12) | 8 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.56 (14) | 0.80 (20) | 0.42 (11) | 0.20 (5.1) | 0.07 (1.8) | 0.04 (1.0) | 0.38 (9.7) | 0.32 (8.1) | 0.32 (8.1) | 0.32 (8.1) | 0.30 (7.6) | 0.45 (11) | 4.18 (106) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.51) | 0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 25.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 45.1 | 39.6 | 33.1 | 25.0 | 21.3 | 16.5 | 21.1 | 25.6 | 25.0 | 28.8 | 37.2 | 45.0 | 30.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 22.1 (−5.5) | 23.7 (−4.6) | 23.9 (−4.5) | 24.1 (−4.4) | 28.2 (−2.1) | 30.9 (−0.6) | 40.6 (4.8) | 44.1 (6.7) | 37.0 (2.8) | 30.4 (−0.9) | 25.3 (−3.7) | 22.3 (−5.4) | 29.4 (−1.5) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 245.2 | 246.7 | 314.6 | 346.1 | 388.1 | 401.7 | 390.9 | 368.5 | 337.1 | 304.4 | 246.0 | 236.0 | 3,825.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 79 | 81 | 85 | 88 | 89 | 92 | 88 | 88 | 91 | 87 | 80 | 78 | 86 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[31] [33] [32] | |||||||||||||

Nearby communities

- Boulder City, incorporated

- Enterprise, unincorporated

- Henderson, incorporated

- Lone Mountain, unincorporated

- North Las Vegas, incorporated

- Paradise, unincorporated

- Spring Valley, unincorporated

- Summerlin South, unincorporated

- Sunrise Manor, unincorporated

- Whitney, unincorporated

- Winchester, unincorporated

Neighborhoods

- Downtown

- The Lakes

- Summerlin

- West Las Vegas

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 25 | — | |

| 1910 | 800 | 3,100.0% | |

| 1920 | 2,304 | 188.0% | |

| 1930 | 5,165 | 124.2% | |

| 1940 | 8,422 | 63.1% | |

| 1950 | 24,624 | 192.4% | |

| 1960 | 64,405 | 161.6% | |

| 1970 | 125,787 | 95.3% | |

| 1980 | 164,674 | 30.9% | |

| 1990 | 258,295 | 56.9% | |

| 2000 | 478,434 | 85.2% | |

| 2010 | 583,756 | 22.0% | |

| 2020 | 641,903 | 10.0% | |

| source:[42] [43] 2010–2010[5] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2010[44] | 2000[45] | 1990[46] | 1970[46] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 62.1% | 69.9% | 78.4% | 87.6% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 47.9% | 58.0% | 72.1% | 83.1%[47] |

| Black or African American | 11.1% | 10.4% | 11.4% | 11.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 31.5% | 23.6% | 12.5% | 4.6%[47] |

| Asian | 6.1% | 4.8% | 3.6% | 0.7% |

Map of racial distribution in Las Vegas, 2010 U.S. Census. Each dot is 25 people: White , Black , Asian , Hispanic , or Other (yellow)

According to the 2010 Census, the racial composition of Las Vegas was as follows:[48]

- White: 62.1% (Non-Hispanic Whites: 47.9%; Hispanic Whites: 14.2%)

- Black or African American: 11.1%

- Asian: 6.1% (3.3% Filipino, 0.7% Chinese, 0.5% Korean, 0.4% Japanese, 0.4% Indian, 0.2% Vietnamese, 0.2% Thai)

- Two or more races: 4.9%

- Native American: 0.7%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.6%

Source:[49]

The city's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic Whites,[44] have proportionally declined from 72.1% of the population in 1990 to 47.9% in 2010, even as total numbers of all ethnicities have increased with the population. Hispanics or Latinos of any race make up 31.5% of the population. Of those 24.0% are of Mexican, 1.4% of Salvadoran, 0.9% of Puerto Rican, 0.9% of Cuban, 0.6% of Guatemalan, 0.2% of Peruvian, 0.2% of Colombian, 0.2% of Honduran and 0.2% of Nicaraguan descent. [46]

According to research by demographer William H. Frey, using data from the 2010 United States Census, Las Vegas has the second lowest level of black-white segregation of any of the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the United States, after Tucson, Arizona.[50]

Hawaiians and Las Vegans alike sometimes refer to Las Vegas as the "ninth island of Hawaii" because so many Hawaiians have moved to the city.[51]

The 2010 census showed the city contained 583,756 people, 211,689 households, and 117,538 families residing.[52] The population density was 4,222.5/sq mi (1,630.3/km2). There were 190,724 housing units at an average density of 1,683.3/sq mi (649.9/km2).

As of 2006, there were 176,750 households, of which 31.9% had children under age 18 living with them, 48.3% were married couples living together, 12.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.5% were non-families. 25.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.20.

In the city, the population age distribution was as follows:

- 25.9% under the age of 18

- 8.8% from 18 to 24

- 32.0% from 25 to 44

- 21.7% from 45 to 64

- 11.6% who were 65 years of age or older

The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 103.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 102.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $53,000 and the median income for a family was $58,465.[53] Males had a median income of $35,511 versus $27,554 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,060. About 6.6% of families and 8.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.4% of those under age 18 and 6.3% of those age 65 or over.

According to a 2004 study, Las Vegas has one of the highest divorce rates.[54] [55] The city's high divorce rate is not wholly due to Las Vegans themselves getting divorced. Since divorce is easier in Nevada than in most other states, many people come from across the country for the easier process. Similarly, Nevada marriages are notoriously easy to get. Las Vegas has one of the highest marriage rates of U.S. cities, with many licenses issued to people from outside the area (see Las Vegas weddings).

Economy

The primary drivers of the Las Vegas economy are tourism, gaming, and conventions, which in turn feed the retail and restaurant industries.

Tourism

The major attractions in Las Vegas are the casinos and the hotels, although in recent years other new attractions have begun to emerge.

Most casinos in the downtown area are located on Fremont Street, with The STRAT Hotel, Casino & Skypod as one of the few exceptions. Fremont East, adjacent to the Fremont Street Experience, was granted variances to allow bars to be closer together, similar to the Gaslamp Quarter of San Diego, the goal being to attract a different demographic than the Strip attracts.

Downtown casinos

The Golden Gate Hotel and Casino, located downtown along the Fremont Street Experience, is the oldest continuously operating hotel and casino in Las Vegas; it opened in 1906 as the Hotel Nevada.

The year 1931 marked the opening of the Northern Club (now the La Bayou).[56] [57] The most notable of the early casinos may have been Binion's Horseshoe (now Binion's Gambling Hall and Hotel) while it was run by Benny Binion.

Boyd Gaming has a major presence downtown operating the California Hotel & Casino, the Fremont Hotel & Casino, and the Main Street Casino. The Four Queens also operates downtown along the Fremont Street Experience.

Downtown casinos that have undergone major renovations and revitalization in recent years include the Golden Nugget Las Vegas, The D Las Vegas (formerly Fitzgerald's), the Downtown Grand Las Vegas (formerly Lady Luck), the El Cortez Hotel & Casino, and the Plaza Hotel & Casino.[58]

Las Vegas Strip

The center of the gambling and entertainment industry is located on the Las Vegas Strip, outside the city limits in the surrounding unincorporated communities of Paradise and Winchester in Clark County. The largest and most notable casinos and buildings are located there.[59]

Development

When The Mirage opened in 1989, it started a trend of major resort development on the Las Vegas Strip outside of the city. This resulted in a drop in tourism in the downtown area, but many recent projects have increased the number of visitors to downtown.

An effort has been made by city officials to diversify the economy by attracting health-related, high-tech and other commercial interests. No state tax for individuals or corporations, as well as a lack of other forms of business-related taxes, have aided the success of these efforts.[60]

The Fremont Street Experience was built in an effort to draw tourists back to the area and has been popular since its startup in 1995.

The city purchased 61 acres (25 ha) of property from the Union Pacific Railroad in 1995 with the goal of creating a better draw for more people to the downtown area. In 2004, Las Vegas Mayor Oscar Goodman announced plans for Symphony Park, which could include a mixture of offerings, such as residential space and office buildings.

Already operating in Symphony Park is the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health (opened in 2010), The Smith Center for the Performing Arts (opened in 2012) and the DISCOVERY Children's Museum (opened in 2013).[61]

On land across from Symphony Park, the World Market Center Las Vegas opened in 2005. It currently encompasses three large buildings with a total of 5.1 million square feet. Trade shows for the furniture and furnishing industries are held there semiannually.

Also located nearby is the Las Vegas North Premium Outlets. With a second expansion, completed in May 2015, the mall currently offers 175 stores.[62]

City offices moved to a new Las Vegas City Hall in February 2013 on downtown's Main Street. The former City Hall building is now occupied by the corporate headquarters for the major online retailer, Zappos.com, which opened downtown in 2013. Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh has taken an interest in the urban area and has contributed $350 million toward a revitalization effort called the Downtown Project.[63] [64] Projects funded include Las Vegas's first independent bookstore, The Writer's Block.[65]

Other industries

A number of new industries have moved to Las Vegas in recent decades. Online shoe retailer Zappos.com (now an Amazon subsidiary) was founded in San Francisco but by 2013 had moved its headquarters to downtown Las Vegas. Allegiant Air, a low-cost air carrier, launched in 1997 with its first hub at McCarran International Airport and headquarters in nearby Summerlin.

Planet 13 Holdings, a cannabis company, have opened the world's largest cannabis dispensary in Las Vegas at 112,000 sq ft (10,400 m2).[66] [67]

Impact of growth on water supply

A growing population means the Las Vegas Valley used 1.2 billion US gallons (4.5×109 L) more water in 2014 than in 2011. Although water conservation efforts implemented in the wake of a 2002 drought have had some success, local water consumption remains 30 percent more than in Los Angeles, and over three times that of San Francisco metropolitan area residents. The Southern Nevada Water Authority is building a $1.4 billion tunnel and pumping station to bring water from Lake Mead, has purchased water rights throughout Nevada, and has planned a controversial $3.2 billion pipeline across half the state. By law, the Las Vegas Water Service District "may deny any request for a water commitment or request for a water connection if the District has an inadequate supply of water." However, limiting growth on the basis of an inadequate water supply has been unpopular with the casino and building industries.[41]

Culture

The city is home to several museums, including the Neon Museum (the location for many of the historical signs from Las Vegas's mid-20th century heyday), The Mob Museum, the Las Vegas Natural History Museum, the DISCOVERY Children's Museum, the Nevada State Museum and the Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park.

The city is home to an extensive Downtown Arts District, which hosts numerous galleries and events including the annual Las Vegas Film Festival. "First Friday" is a monthly celebration that includes arts, music, special presentations and food in a section of the city's downtown region called 18b, The Las Vegas Arts District.[68] The festival extends into the Fremont East Entertainment District as well.[69] The Thursday evening prior to First Friday is known in the arts district as "Preview Thursday", which highlights new gallery exhibitions throughout the district.[70]

The Las Vegas Academy of International Studies, Performing and Visual Arts is a Grammy award-winning magnet school located in downtown Las Vegas. The Smith Center for the Performing Arts is situated downtown in Symphony Park and hosts various Broadway shows and other artistic performances.

Las Vegas has earned the moniker "Gambling Capital of the World", as the city currently has the largest number of land-based casinos in the world.[71]

Sports

The Las Vegas Valley is the home of three major professional teams: the Vegas Golden Knights of the National Hockey League, an expansion team that began play in the 2017–18 NHL season at T-Mobile Arena in nearby Paradise,[72] the Las Vegas Raiders of the National Football league who relocated from Oakland, California in 2020 and play at Allegiant Stadium in Paradise,[73] and the Las Vegas Aces of the Women's National Basketball Association who play at the Mandalay Bay Events Center.

Two minor league sports teams play in the Las Vegas area. The Las Vegas Aviators of the Triple-A West, the Triple-A farm club of the Oakland Athletics, play at Las Vegas Ballpark in nearby Summerlin.[74] The Las Vegas Lights FC of the United Soccer League, play in Cashman Field in Downtown Las Vegas.[75] [76]

The mixed martial arts promotion, Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), is headquartered in Las Vegas and also frequently holds fights in the city at T-Mobile Arena and at the UFC Apex training facility near the headquarters.[77]

List of teams

Major professional teams

| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Established | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Las Vegas Raiders | Football | NFL | Allegiant Stadium (65,000) | 2020 | 3 |

| Vegas Golden Knights | Ice Hockey | NHL | T-Mobile Arena (17,500) | 2017 | 0 |

| Las Vegas Aces | Women's basketball | WNBA | Michelob Ultra Arena (12,000) | 2018 | 0 |

Minor professional teams

| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Established | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Las Vegas Aviators | Baseball | MiLB (Triple-A West) | Las Vegas Ballpark (10,000) | 1983 | 2 |

| Las Vegas Royals | Basketball | ABA | 2020 | 0 | |

| Vegas Ballers | TBL | Tarkanian Basketball Center (N/A) | 0 | ||

| Henderson Silver Knights | Ice hockey | AHL | Orleans Arena (7,773) Dollar Loan Center (6,019) | 0 | |

| Las Vegas Lights FC | Soccer | USLC | Cashman Field (9,334) | 2018 | 0 |

| Sin City Trojans | Women's football | WFA | Desert Pines High School (N/A) | 2008 | 0 |

| Vegas Knight Hawks | Indoor football | IFL | Dollar Loan Center (6,019) | 2021 | 0 |

| Las Vegas NLL team | Box lacrosse | NLL | Michelob Ultra Arena (12,000) | 0 |

Amateur teams

| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Established | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegas Jesters | Ice hockey | MWHL | City National Arena (600) | 2012 | 0 |

| Las Vegas Thunderbirds | USPHL | 2019 | 0 | ||

| Las Vegas Legends | Soccer | NPSL | Peter Johann Memorial Field (2,500) | 2021 | 0 |

College teams

| School | Team | League | Division | Primary Conference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) | UNLV Rebels | NCAA | NCAA Division I | Mountain West |

| College of Southern Nevada (CSN) | CSN Coyotes | NJCAA | NJCAA Division I | Scenic West |

Parks and recreation

Las Vegas has 68 parks. The city owns the land for, but does not operate, four golf courses: Angel Park Golf Club, Desert Pines Golf Club, Durango Hills Golf Club, and the Las Vegas Municipal Golf Course. It is also responsible for 123 playgrounds, 23 softball fields, 10 football fields, 44 soccer fields, 10 dog parks, six community centers, four senior centers, 109 skate parks, and six swimming pools.[78]

Government

The city of Las Vegas government operates as a council–manager government. The Mayor sits as a Council member-at-large and presides over all of the city council meetings. If the Mayor cannot preside over a City Council meeting, then the Mayor Pro-Tem is the presiding officer of the meeting until the Mayor returns to his/her seat. The City Manager is responsible for the administration and the day-to-day operations of all municipal services and city departments. The City Manager maintains intergovernmental relationships with federal, state, county and other local governments.

Much of the Las Vegas metropolitan area is split into neighboring incorporated cities or unincorporated communities. Approximately 700,000 people live in unincorporated areas governed by Clark County, and another 465,000 live in incorporated cities such as North Las Vegas, Henderson and Boulder City. Las Vegas and Clark County share a police department, the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, which was formed after a 1973 merger of the Las Vegas Police Department and the Clark County Sheriff's Department. North Las Vegas, Henderson, Boulder City and some colleges have their own police departments.

A Paiute Indian reservation occupies about 1 acre (0.40 ha) in the downtown area.

Las Vegas, home to the Lloyd D. George Federal District Courthouse and the Regional Justice Center, draws numerous companies providing bail, marriage, divorce, tax, incorporation and other legal services.

City council

| Name | Position | Party | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carolyn Goodman | Mayor | Independent | [79] | Replaced her husband, Oscar Goodman, who was term-limited |

| Brian Knudsen | 1st Ward Council member | Democratic | [80] [81] | |

| Victoria Seaman | 2nd Ward Council member | Republican | [82] [81] | |

| Olivia Diaz | 3rd Ward Council member | Democratic | [83] [81] | |

| Stavros S. Anthony | 4th Ward Council member | Republican | [84] | Mayor Pro Tem |

| Cedric Crear | 5th Ward Council member | Democratic | [85] [86] | |

| Michele Fiore | 6th Ward Council member | Republican | [87] |

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Primary and secondary public education is provided by the Clark County School District, which is the fifth most populous school district in the nation. Students totaled 314,653 in grades K-12 for school year 2013–2014.[88]

Colleges and universities

The College of Southern Nevada (the third largest community college in the United States by enrollment) is the main higher education facility in the city. Other institutions include the University of Nevada School of Medicine, with a campus in the city, and the for-profit private school Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts. Educational opportunities exist around the city; among them are the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and Nevada State College run by the Nevada System of Higher Education, Desert Research Institute, The International Academy of Design & Technology Las Vegas and Touro University Nevada.

Media

Newspapers

Las Vegas Review-Journal sign

- Las Vegas Review-Journal, the area's largest daily newspaper, is published every morning. It was formed in 1909 but has roots back to 1905. It is the largest newspaper in Nevada and is ranked as one of the top 25 newspapers in the United States by circulation. In 2000, the Review-Journal installed the largest newspaper printing press in the world. It cost $40 million, weighs 910 tons and consists of 16 towers.[89] The newspaper is owned by casino magnate Sheldon Adelson, who purchased it for $140 million in December 2015. In 2018, the Review-Journal received the Sigma Delta Chi Award from the Society of Professional Journalists for reporting the Oct 1 mass shooting on the Las Vegas Strip. In 2018, Editor and Publisher magazine named the Review-Journal as one of 10 newspapers in the United States "doing it right".[90]

- Las Vegas Sun, a daily 8-page newspaper independently published but the print edition distributed as a section inside the Review-Journal. The Sun is owned by the Greenspun family and is affiliated with Greenspun Media Group. It was founded independently in 1950 and in 1989 entered into a Joint Operating Agreement with the Review-Journal, which runs through 2040. The Sun has been described as "politically liberal."[91] In 2009, the Sun was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for coverage of the high death rate of construction workers on the Las Vegas Strip amid lax enforcement of regulations.

- Las Vegas Weekly is a free alternative weekly newspaper based in Henderson, Nevada. It covers Las Vegas arts, entertainment, culture and news. Las Vegas Weekly was founded in 1992 and is published by Greenspun Media Group.

Broadcast

Las Vegas is served by 22 television stations and 46 radio stations. The area is also served by two NOAA Weather Radio transmitters (162.55 MHz located in Boulder City and 162.40 MHz located on Potosi Mountain).

- Radio stations in Las Vegas

- Television stations in Las Vegas

Magazines

- Desert Companion

- Las Vegas Weekly

- Luxury Las Vegas

Transportation

Regional Transportation Commission (RTC) provides public transportation.

Inside Terminal 3 at McCarran International Airport in Paradise

RTC Transit is a public transportation system providing bus service throughout Las Vegas, Henderson, North Las Vegas and other areas of the valley. Inter-city bus service to and from Las Vegas is provided by Greyhound, BoltBus, Orange Belt Stages, Tufesa, and several smaller carriers.[92] Amtrak trains have not served Las Vegas since the service via the Desert Wind at Las Vegas station ceased in 1997, but Amtrak California operates Thruway Motorcoach dedicated service between the city and its passenger rail stations in Bakersfield, California, as well as Los Angeles Union Station via Barstow.[93]

The Union Pacific Railroad is the only Class I railroad providing rail freight service to the city. Until 1997, the Amtrak Desert Wind train service ran through Las Vegas using the Union Pacific Railroad tracks.

In March 2010, the RTC launched bus rapid transit link in Las Vegas called the Strip & Downtown Express with limited stops and frequent service that connects downtown Las Vegas, the Strip and the Las Vegas Convention Center. Shortly after the launch, the RTC dropped the ACE name.[94]

In 2016, 77.1 percent of working Las Vegas residents (those living in the city, but not necessarily working in the city) commuted by driving alone. About 11 percent commuted via carpool, 3.9 percent used public transportation, and 1.4 percent walked. About 2.3 percent of Las Vegas commuters used all other forms of transportation, including taxi, bicycle, and motorcycle. About 4.3 of working Las Vegas residents worked at home.[95] In 2015, 10.2 percent of city of Las Vegas households were without a car, which increased slightly to 10.5 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Las Vegas averaged 1.63 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8 per household.[96]

With some exceptions, including Las Vegas Boulevard, Boulder Highway (SR 582) and Rancho Drive (SR 599), the majority of surface streets in Las Vegas are laid out in a grid along Public Land Survey System section lines. Many are maintained by the Nevada Department of Transportation as state highways. The street numbering system is divided by the following streets:

- Westcliff Drive, US 95 Expressway, Fremont Street and Charleston Boulevard divide the north–south block numbers from west to east.

- Las Vegas Boulevard divides the east–west streets from the Las Vegas Strip to near the Stratosphere, then Main Street becomes the dividing line from the Stratosphere to the North Las Vegas border, after which the Goldfield Street alignment divides east and west.

- On the east side of Las Vegas, block numbers between Charleston Boulevard and Washington Avenue are different along Nellis Boulevard, which is the eastern border of the city limits.

Interstates 15, 515, and US 95 lead out of the city in four directions. Two major freeways – Interstate 15 and Interstate 515/U.S. Route 95 – cross in downtown Las Vegas. I-15 connects Las Vegas to Los Angeles, and heads northeast to and beyond Salt Lake City. I-515 goes southeast to Henderson, beyond which US 93 continues over the Mike O'Callaghan–Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge towards Phoenix, Arizona. US 95 connects the city to northwestern Nevada, including Carson City and Reno. US 93 splits from I-15 northeast of Las Vegas and goes north through the eastern part of the state, serving Ely and Wells. US 95 heads south from US 93 near Henderson through far eastern California. A partial beltway has been built, consisting of Interstate 215 on the south and Clark County 215 on the west and north. Other radial routes include Blue Diamond Road (SR 160) to Pahrump and Lake Mead Boulevard (SR 147) to Lake Mead.

East–west roads, north to south[97]

- North–south roads, west to east

McCarran International Airport handles international and domestic flights into the Las Vegas Valley. The airport also serves private aircraft and freight/cargo flights. Most general aviation traffic uses the smaller North Las Vegas Airport and Henderson Executive Airport.

Notable people

See also

- 2017 Las Vegas shooting

- List of films set in Las Vegas

- List of films shot in Las Vegas

- List of Las Vegas casinos that never opened

- List of mayors of Las Vegas

- List of television shows set in Las Vegas

- Radio stations in Las Vegas

- Television stations in Las Vegas

Notes

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

References

- ^ Merriam Webster's Geographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Merriam-Webster. 1997. p. 633. ISBN978-0877795469.

- ^ "Words and Their Stories: Nicknames for New Orleans and Las Vegas". VOA News. March 13, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ Lovitt, Rob (December 15, 2009). "Will the real Las Vegas please stand up?". NBC News . Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau . Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Las Vegas city, Nevada". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Jones, Charisse (August 21, 2013). "Top convention destinations: Orlando, Chicago, Las Vegas". USA Today.

- ^ Trejos, Nancy (January 17, 2014). "AAA chooses Five Diamond hotels, restaurants for 2014". USA Today . Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ "Top 5 Cities to Get Hired in Hospitality". Hcareers.com. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ "Overseas Visitation Estimates for U.S. States, Cities, and Census Regions: 2013" (PDF). International Visitation in the United States. US Office of Travel and Tourism Industries, US Department of Commerce. May 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014. [ dead link ]

- ^ "World's Most-Visited Tourist Attractions". Travel + Leisure. November 10, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ Schwartz, David G. (December 10, 2018). "Why Las Vegas Is Still America's Most Sinful City". Forbes . Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Las Vegas city, Nevada". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ^ Schoenmann, Joe (February 3, 2010). "Vegas not alone in wanting in on .vegas". Las Vegas Sun.

- ^ "County Turns 100 July 1, Dubbed 'Centennial Day'" (Press release). Clark County, Nevada. June 23, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ a b "History". City of Las Vegas. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Lake, Richard (December 17, 2008). "Road Warrior Q&A: Foliage removed for widening". Las Vegas Review-Journal . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Ponce, Victor Miguel. "Las Vegas, how did Las Vegas get its name, groundwater depletion". San Diego State University . Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "History of Las Vegas". Las Vegas Online Entertainment Guide . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Land, Barbara; Land, Myrick (March 1, 2004). A Short History of Las Vegas. University of Nevada Press. p. 4. ISBN978-0874176438 . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "FAQs/History". Clark County, Nevada . Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1941). Origin of Place Names: Nevada (PDF). Works Progress Administration. p. 16.

- ^ "Home". United States Air Force Thunderbirds. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ a b Simon, Steven; Bouville, Andre (January–February 2006). "Fallout from Nuclear Weapons Tests and Cancer Risks". American Scientist. 94 (1): 48. doi:10.1511/2006.57.48. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

Exposures 50 years ago still have health implications today that will continue into the future...Deposition...generally decreases with distance from the test site in the direction of the prevailing wind across North America, although isolated locations received significant deposition as a result of rainfall. Trajectories of the fallout debris clouds across the U.S. are shown for four altitudes. Each dot indicates six hours.

- ^ Brown, Patricia Leigh (January 13, 2005). "A Neon Come-Hither, Still Able to Flirt". The New York Times . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Segall, Eli; Subrina Hudson (October 22, 2020). "Zappos' new landlord is a familiar face". Las Vegas Review-Journal . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Geography of Las Vegas, Nevada". geography.about.com. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "Flood control a success". Las Vegas Review-Journal. December 28, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Loss-Estimation Modeling of Earthquake Scenarios for Each County in Nevada Using HAZUS-MH" (PDF). Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology. Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology/University of Nevada, Reno. February 23, 2006. p. 65. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

"Probability of an earthquake of magnitude 6.0 or greater occurring within 50 km in 50 years (from USGS probabilistic seismic hazard analysis) 10–20% chance for Las Vegas area, magnitude 6".

- ^ a b c d e f g "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ a b "WMO Climate Normals for LAS VEGAS/MCCARRAN, NV 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ a b "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Osborn, Liz. "Cities With Low Humidity in the USA". Current Results . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Sauceda, Daniel O. (December 2014). Observed and Simulated Urban Heat Island and Urban Cool Island in Las Vegas (PDF) (Thesis). University of Nevada, Reno. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Montero, David. "It just snowed in Vegas and likely will again this week. That isn't normal". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ NWS Las Vegas [@NWSVegas] (February 21, 2019). "Las Vegas official snowfall for Feb 20th is 0.5 inches. This breaks a daily snowfall record for this date" (Tweet). Retrieved July 20, 2019 – via Twitter.

- ^ Michor, Max (February 23, 2018). "Las Vegas Valley gets first touch of white winter". Las Vegas Review-Journal . Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Hansen, Kyle B. (August 26, 2011). "Photos: Remembering snowstorms in Las Vegas offers retreat from the heat". Las Vegas Sun . Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ "Las Vegas NV Highest Temperature Each Year". Current Results . Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Lustgarten, Abrahm (June 2, 2015). "Las Vegas Water Chief Pat Mulroy Preached Conservation, But Pushed Growth". ProPublica . Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Las Vegas city, Nevada; count revision of 01-07-2018". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 159.

- ^ a b "Las Vegas (city), Nevada". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic or Latino: 2000". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Nevada – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b From 15% sample

- ^ "Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS)". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Las Vegas, Nevada 2010 Census Profile". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ Frey, William H. (July 24, 2018). Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America (Second ed.). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 177. ISBN978-0-8157-2398-1 . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Las Vegas: Bright Lights, Big City, Small Town". State of the Reunion. Autumn 2012. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ "Las Vegas, Nevada Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts". Census Viewer . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2006 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars): Las Vegas". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Most Stressful US City". City Mayors. January 10, 2004. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ Blakeslee, Sandra (December 16, 1997). "Health: Suicide Rate Higher in 3 Gambling Cities, Study Says". The New York Times . Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ Rinella, Heidi Knapp (July 27, 2000). "New book raises questions about Silver State". Las Vegas Review-Journal.

- ^ "Fremont Street Experience Brings Downtown Las Vegas into Next Century". Fremont Street Experience. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ 2013 Fiscal Year in Review, city of Las Vegas Economic and Urban Development Projects, "A New Downtown Emerges."

- ^ Koch, Ed; Manning, Mary; Toplikar, Dave (May 15, 2008). "Showtime: How Sin City evolved into 'The Entertainment Capital of the World'". Las Vegas Sun . Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ "Las Vegas Redevelopment Agency". City of Las Vegas . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Symphony Park, Las Vegas". Las Vegas Economic and Urban Development Agency. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ "Premium Outlets: Las Vegas". Simon Property Group . Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Downtown Project – Revitalizing Downtown Las Vegas". Downtownproject.com . Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Pratt, Timothy (October 19, 2012). "What Happens in Brooklyn Moves to Vegas". The New York Times Magazine . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Sieroty, Chris. "Despite E-Books, Independent Bookstore Gambling on Downtown Las Vegas". KNPR News. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2020. CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- ^ Im, Jimmy (November 3, 2018). "The world's largest cannabis dispensary just opened in Vegas—and it has an entertainment complex attached". CNBC . Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ Chen, Angela (November 15, 2018). "We visited the world's largest cannabis dispensary". The Verge . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "18b Las Vegas Art District". 18b.org. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "First Friday Main Menu". First Friday Las Vegas Network . Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Preview Thursday". 18b.org. Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017. CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ "Las Vegas Gambling Capital". vegasmobilecasino.co.uk. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ Heitner, Darren (June 22, 2016). "The NHL Leads the Way in Bringing Pro Sports to Las Vegas". Inc. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Gutierrez, Paul (March 27, 2017). "NFL owners vote 31–1 to approve Raiders move to Las Vegas". ESPN . Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Bowers, Nikki (April 17, 2018). "Las Vegas 51s to rebrand, rename team". KLAS News.

- ^ "Las Vegas Lights FC". www.lasvegaslightsfc.com.

- ^ "Home". United Soccer League.

- ^ "UFC Apex Officially Opens in Las Vegas". UFC.com.

- ^ "Find Parks and Facilities". City of Las Vegas. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ "2011 Municipal Primary Election April 5, 2011". Clark County, Nevada. April 5, 2011. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ "Brian Knudsen". LGBTQ Victory Fund. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Miranda (July 3, 2019). "Diverse new members sworn in to Las Vegas City Council". Las Vegas Sun . Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Willson, Miranda (June 11, 2019). "Knudsen, Diaz and Seaman win races, reshaping the Las Vegas City Council". Las Vegas Sun . Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Valley, Jackie (June 11, 2019). "Diaz, Knudsen and Seaman to join Las Vegas City Council after winning municipal races". The Nevada Independent . Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ "Stavros S. Anthony". Ballotpedia . Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "Cedric Crear". Ballotpedia . Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ Searer, Kirsten (April 2, 2004). "At least four vie for Neal seat". Las Vegas Sun . Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ Lupiani, Joyce (July 3, 2019). "Michele Fiore named Mayor Pro Tem for Las Vegas". KTNV News . Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Source: city of Las Vegas Planning Department, MAY 2014.

- ^ Scheid, Jenny. "New presses are the worlds's largest". Las Vegas Review-Journal . Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Yang, Nu; Ruiz, Jesus. "10 Newspapers That Do It Right 2018: Recognizing Success in Pioneering Newsrooms, Advertising Growth and Community Engagement". Editor & Publisher. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Rainey, James. "Sleeping with the enemy newspaper". Los Angeles Times. p. E1. Retrieved March 8, 2006.

- ^ "Nevada Tables". American Intercity Bus Riders Association.

- ^ "California-Train and Thruway service" (PDF). Amtrak . Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ Green, Steve (August 17, 2011). "Lawsuit prompts RTC to drop 'ACE' name from bus lines". Las Vegas Sun . Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ "Means of Transportation to Work by Age". Census Reporter . Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ Most arterial roads are shown, as indicated on the Nevada Department of Transportation's Roadway functional classification: Las Vegas urbanized area map Archived April 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

Further reading

- Brigham, Jay. "Reno, Las Vegas, and the Strip: A Tale of Three Cities." Western Historical Quarterly 46.4 (2015): 529–530.

- Chung, Su Kim (2012). Las Vegas Then and Now, Holt: Thunder Bay Press, ISBN 978-1-60710-582-4

- Moehring, Eugene P. Resort City in the Sunbelt: Las Vegas, 1930–2000 (2000).

- Moehring, Eugene, "The Urban Impact: Towns and Cities in Nevada's History," Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 57 (2014): 177–200.

- Rowley, Rex J. Everyday Las Vegas: Local Life in a Tourist Town (2013)

- Stierli, Martino (2013). Las Vegas in the Rearview Mirror: The City in Theory, Photography, and Film, Los Angeles: Getty Publications, ISBN 978-1-60606-137-4

- Venturi, Robert (1972). Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form, Cambridge: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-26272-006-9

External links

- Official website

- "The Making of Las Vegas" (historical timeline)

- Geologic tour guide of the Las Vegas area from American Geological Institute

- National Weather Service Forecast – Las Vegas, NV

Internships For Video Game Design Las Vegad

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Las_Vegas

Posted by: allbrightwatermint.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Internships For Video Game Design Las Vegad"

Post a Comment